Chances are if you have a favorite food, salt and sugar are high on the ingredient list. We crave sweet and salty foods, and food manufacturers and restaurants have been exploiting this preference for decades for one simple reason: tasty food sells. In fact, food companies use 5 billion pounds of salt each year!1

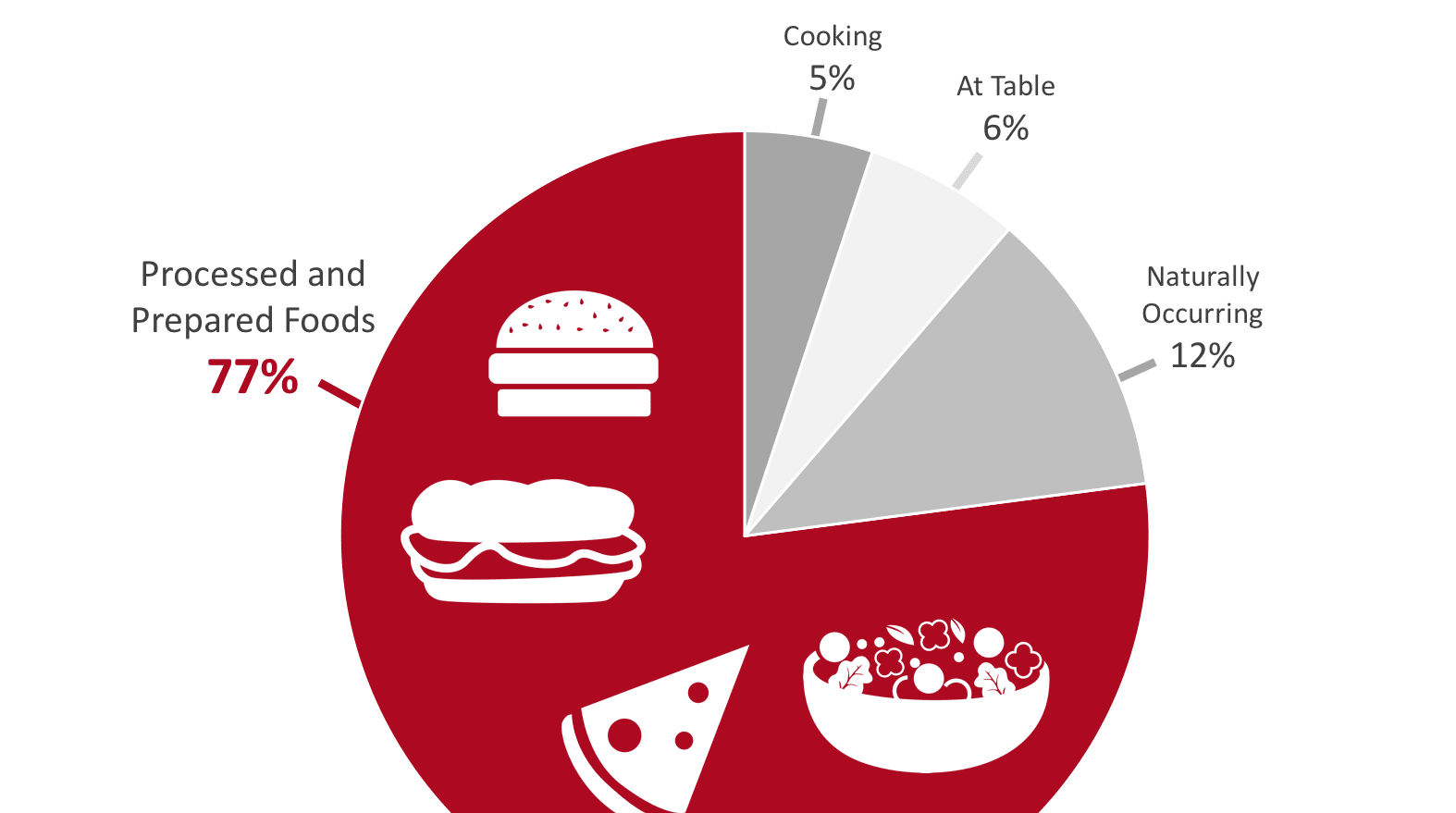

Salt is composed of 40% sodium and 60% chloride and though both nutrients are essential in our daily diet, we are consuming far more sodium than is needed or even healthy.2 The average daily intake of sodium for all Americans over one year old is estimated to be 3,440 milligram (mg), which works out to be about 1.5 teaspoons of salt and far exceeds the upper limit recommended for all age groups(depending on the agency making the recommendation, maximum intake of sodium should be between 1500 to 2300 mg a day).3,4 Below is a breakdown of estimated sodium intake by age in the United States.5

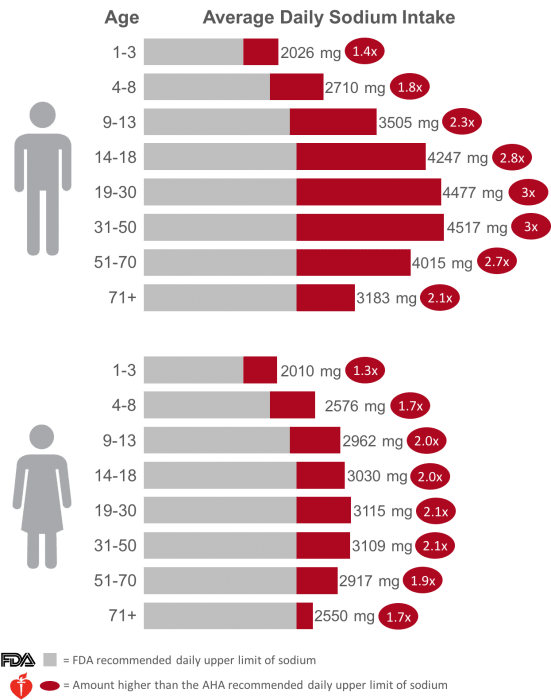

It is pretty clear that we, as a nation, like to eat salty foods. However, this high sodium intake is not from adding salt to food while cooking or even to the foods we eat at the dinner table. Where is all the sodium we eat coming from? Below is a chart categorizing the sources of sodium in the American diet.6

The majority of our daily sodium intake comes from processed (bought at a grocery store) or commercially prepared (restaurants, fast food) foods.6 Our increased frequency of dining out and shift away from cooking meals from scratch has dramatically increased our sodium intake. And while this has helped save us time each day, this convenience comes with a health cost.

Why should we care about our high sodium intake?

Consuming too much sodium is a major cause of high blood pressure.

It is estimated that 1 in 3 Americans have high blood pressure (BP) and there is overwhelming scientific evidence demonstrating that excess dietary sodium intake is the major cause of high blood pressure.7,8 Conversely, reducing sodium intake has been shown to have a dramatic impact on lowering blood pressure.8 Increased blood pressure is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including stroke, heart attack and even death.9

Consuming too much sodium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM, formerly called the Institute of Medicine) published a report in 2013 analyzing the association of sodium intake with direct health outcomes (not just indicators of health out comes, such as blood pressure). While the committee found the quantity and quality of studies analyzing the health effects of sodium consumption to be less than optimal, they were able to determine that there was a “positive relationship between higher levels of sodium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease.”9 The NAM considers “higher” sodium levels to be above 2300 mg per day.

It is worth noting that the Institute of Medicine report found that there was not sufficient scientific evidence to determine that eating less than 2300 mg of sodium a day had either a positive or negative impact on cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, their recommendation remains consistent with the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines that all people should target consuming an upper limit of 2300 mg of sodium a day.

Other potential health effects from consuming too much sodium.

In addition to elevated blood pressure and its association with increased risk of CVD, excess sodium intake has been associated with increased risk of kidney damage, fibrosis of the heart and arteries, and gastric cancer.10,11 However, when the previously mentioned Institue of Medicine report review the clinical data for these studies, they found that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to support a cause and effect relationship between excessive sodium intake and any of these health outcomes.9

How can you reduce your daily sodium intake?

With 9 out of 10 Americans (adults and children alike) consuming more than the recommended daily upper intake of sodium, reducing the amount of sodium we consume is a key public health concern.12 Strategies to lower sodium intake include:

1. Cook more meals at home.

77% of our daily sodium intake comes from eating prepared foods or those purchased at restaurants, it is important to start preparing more meals at home. However, when preparing meals at home, we must be aware of the ingredients we are using and prioritize cooking foods from scratch wherever possible and not simply reheating sodium laden convenience foods.

2. Purchase fresh or frozen foods without added sauces or seasoning.

Stocking up on fresh and frozen foods is a great way to start lowering your sodium intake. Fresh produce and meat should have minimal levels of natural sodium and sodium from added salt. If purchasing frozen foods, always read ingredients to ensure there is no added salt. There are many quick meals you can prepare quickly that are low in sodium and yet still delicious.

3. Purchase low- or no- sodium processed foods.

Before you buy a processed food, look at the Nutrition Facts label and evaluate the sodium content of a food serving. How much does it contribute to your daily target of ≤ 1500 to 2300 mg of sodium? When possible, choose a low-sodium or no-sodium options. Be cautious with common staple items that are loaded with added sodium including: anything tomato based (pasta sauce, soup, juice), processed meats (luncheon meats, hot dogs, sausages), soups, chips, crackers, and even some breakfast cereals.

Final thoughts about dietary sodium

Reducing the amount of sodium we eat daily is one way to improve our long-term health. The first step is to realize just how much sodium is in the foods we are eating. If your daily sodium intake is higher than 2300 mg a day (and most of ours is), start reducing it by replacing processed foods with low-salt or, better yet, home cooked versions. Try to make informed food choices and help your family do the same.

References:

- Salt, Sugar, Fat. Michael Moss, 2013 (link)

- What We Eat, Marion Nestle, 2006 (link)

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020, Eighth Ed. (link)

- Morton Plain Table Salt Nutrition Facts, Morton Website (link)

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020, Eighth Ed. (link)

- Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr. 1991;10(4):383–393 (link)

- High Blood Pressure Statistical Fact Sheet, 2013, American Heart Association Website (link)

- WASH-world action on salt and health. Kidney Int. 2010;78:745-753. (link)

- Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence, Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013 (link)

- The Importance of Population-Wide Sodium Reduction as a Means to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke, A Call to Action From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1138-1143. (link)

- Sodium, Blood Pressure, and Cardiovascular Health, Further evidence supporting the American Heart Association Sodium Reduction Recommendations. Circulation. 2012;126:2880-2889 (link)

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control Website, Jan 8 2016 (link)

- Validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data. Archer E, Hand GA, Blair SN., 1971-2010. PLoS One. 2013; 8(10):e76632. (link)

Note: The data referenced in the charts in this post came from “What We Eat in America” (WWEIA), a component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination (NHANES) survey. NHANES is a national survey conducted every few years to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States (more information). The data collected for WWEIA / NHANES are self-reported where the participant recalls what they ate in the past 24-hrs and this information is interpreted by an interviewer. In an analysis of historical NHANES data, researchers have shown that the self reported data from a majority of the respondents were not “physiologically plausible”.13 In other words, the participants severely under-reported their daily energy intake. So it is quite likely that actual sodium intake is higher than reported.